No longer so attached to the idea of Greek ethnicity

By Angelo Tramountanis.

Young people in Greece may be bucking some well-established trends about Greek identity and its meaning, according to research by the Open Society European Policy Institute and d|part

Until the early 1990s and the first influx of immigrants, Greece saw itself as almost exclusively ethnic Greek, mostly Eastern Orthodox Christians. Anything different was perceived as foreign and regarded as a potential threat.

According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, two-thirds of Greeks consider that “real” Greeks share the same customs and traditions, and half believe that being Christian is essential. In another survey by the research group diaNEOsis in 2018, 54 percent of respondents said that to be considered Greek, a person has to adopt Greek customs and the way of life.

Yet Greece can no longer claim, if indeed it was ever the case, to be a homogenous country. The arrival of immigrants, first from the Balkans and later from Asia and Africa, has given rise to strong anti-immigrant feelings. At the same time, Greece’s young people have been growing up in an increasingly diverse environment. Has this been a determining factor in the changing of their attitudes? And what are the implications of this newly tolerant approach for the open society?

Diminishing importance of ethnic homogeneity

Because modern Greece has been built on the myth of cultural and ethnic homogeneity, it is hardly surprising that nine out of 10 Greeks, as the diaNEOsis survey suggests, believe the country has been welcoming too many immigrants. But new research from this Voices on Values project indicates a possible change in young people’s attitudes.

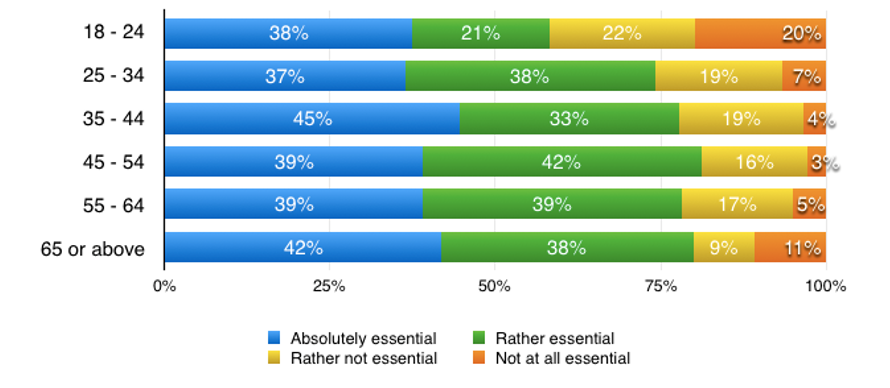

The survey collected data on open and closed society attitudes, asking respondents how essential various attributes were for a good society. To the statement, “That as few immigrants as possible should come to Greece”, 42 percent of those aged 18–25 did not see this as essential (Figure 1). This relatively high percentage is even more striking when compared to responses from older age groups: some 75–81 percent of older people believed that a good society requires as few immigrants as possible.

Figure 1: How essential is the following for a good society? “That as few immigrants as possible come to Greece.”

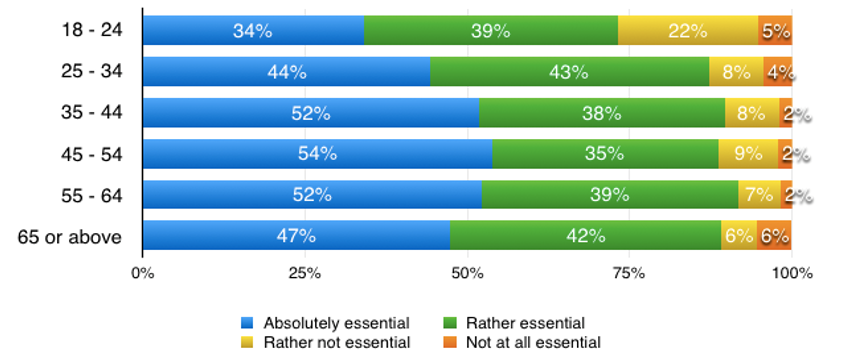

In the statement, “That everyone should live by the national values and norms of Greece”, young Greeks once again demonstrated different attitudes from the older generations (Figure 2). One out of four (27%) of those aged 18–24 didn’t think this way. They are also the age group that is least focussed on this view (only 34% considered it as absolutely essential, compared to at least 44% in the case of 25–35-year-olds).

Figure 2: How essential is the following for a good society? “That everyone lives by the national values and norms of Greece.”

The Eastern Orthodox Church has been a cornerstone of Greece’s modern identity, with only small pockets of other religions, notably the Muslim religious minority in Western Thrace, and a Catholic community in the Cyclades islands. Members of these religious minorities have always been considered ethnic Greeks.

Nowadays, most of the new immigrants to Greece are Muslims, and we have looked at attitudes towards them among different age groups.

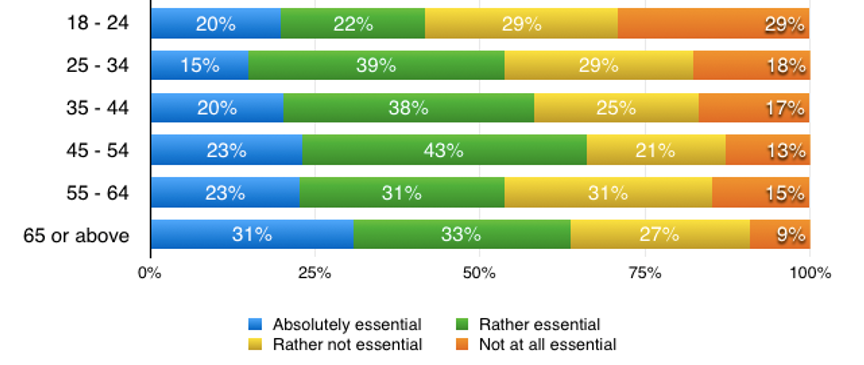

One of the statements people were asked to respond to was whether or not it is essential for a good society “that non-Christians only visibly practise their religion at home or in their places of religious worship” (Figure 3). Our findings were that only 42 percent of the 18–24s agreed, and 58 percent did not. This is a striking difference from all the other age groups, as most of the survey’s respondents felt that non-Christians should not practise their religion publicly.

Figure 3: How essential is the following for a good society? “That non-Christians only practise their religion at home and in their places of religious worship.”

Conclusion: The way forward

Two points are important. The first is that Greece’s founding myth of cultural, ethnic and religious homogeneity appears to be evolving, if gradually. American psychologist Gordon Allport’s Intergroup Contact Theory has demonstrated that when people are born and raised in a multicultural society, their relationships with other young people from different ethnic, cultural and religious backgrounds make them more open and welcoming. This appears to be the case in Greece.

The second consideration is the severe impact of what The Economist recently described as “the deepest depression suffered by any rich country since the second world war.” Its impact was particularly brutal on the younger generation, with youth unemployment peaking at 49.8 percent in 2015, and still the highest in Europe (43.6%). The proportion of young Greeks not in education, employment or training (known as NEETs) was second in 2017 only to Italy (24.2% to 25.5%). The situation for young Greeks is so frustrating that since 2008 more than 420,000 have emigrated, in a clear instance of “brain drain”.

However, and this is significant, according to the Voices on Values data the effects of the economic crisis have not pushed younger Greeks into espousing the anti-immigrant rhetoric of populists and far-right parties like Golden Dawn. If anything, young Greeks appear instead to be embracing open society attributes in a way that sets them apart from the older generations. The common understanding of what it means to be Greek is definitely changing.

Literature

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books

diaNEOsis, (2018), What do Greeks believe: 2018 (Τι πιστεύουν οι Έλληνες: 2018), Retrieved from: https://www.dianeosis.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Ti_Pistevoun_Oi_Ellines_2018_Upd_040618.pdf (last access: 8/8/2018) (In Greek)

PEW Research Center. (2017). What It Takes to Truly Be “One of Us.”, Retrieved from http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/02/01/what-it-takes-to-truly-be-one-of-us/ (last access: 8/8/2018)

Vertovec S., 2007, “Super-diversity and its implications”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30 (6), 1024–1054.

–

Angelo Tramountanis is a researcher at the National Centre for Social Research (EKKE) in Athens.

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.