Divided, but not tearing each other apart

By Magali Mohr.

Young people in Germany are polarised in their support or rejection of the open society, according to research by the Open Society European Policy Institute and d|part.

Young people in Germany project contradictory images. On the one hand, they are said to value stability, on the other they are seen as passionate progressives.

The pragmatic “Merkel generation” in adulthood has known only one chancellor, and surveys and media regularly portray a yearning for stability and order. Unlike previous generations, they seek normality and mainstream values. They want to fit in (Calmbach et al. 2016:475).

At the same time, they are strong advocates of openness, tolerance and the Willkommenskultur towards immigrants. When hundreds of thousands of asylum-seekers arrived in Germany in the summer of 2015, young Germans made up the largest numbers of volunteers (Karakayali & Kleist, 2016:12–13). Few of them appear to be attracted to nationalism or patriotism (Calmbach et al. 2016:472), and they are more wary of xenophobia than immigration.

What do these contradictions mean for the open society? Are there two distinct groups of young Germans, each with their own views? Or is this a deeply divided generation? Our Voices on Values survey looks at the values of the under-25-year-olds to shed light on this apparent paradox.

People in the survey were asked which attributes were more, less or equally important to what they considered a good society. They were also asked to trade off 14 attributes usually considered to be those of an open society – freedom of religion, freedom of expression, protection of minority rights – for 14 items that might restrict these freedoms – social cohesion, political stability, economic well-being.

Divided but not split asunder

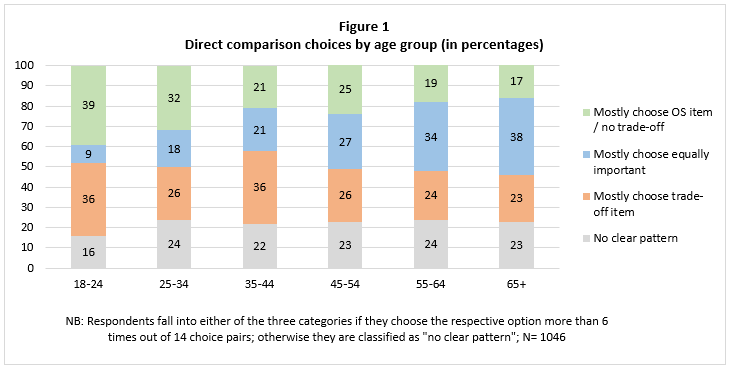

Examining how Germans of all ages responded to these trade-off questions we found that those aged 18 to 24 appeared divided but not to the point of being torn asunder. Groups of young people apparently have distinct views on the open society. Some 39 percent of 18-to-24-year-olds refuse to trade off open society attributes. They believe in values like freedom of expression and the protection of minorities. Some 36 percent, however, are consistently in favour of policies promoting social cohesion, political stability and economic wellbeing, when having to choose against increased migration, religious tolerance and other open society attributes.

This pattern is unique to young people (Figure 1). Only 9 percent of 18-to-24-year-old Germans said that both issues in the trade-off were equally important for a good society, while more than a third of over 55-year-olds consistently thought so. Jan Eichhorn has concluded elsewhere that, for the overall population, we cannot assume a strong schism between open and closed society views, because of the large group of “in-betweens” who favour both. The youngest age group, however, seem to be more willing to argue both ways.

Not all young Germans value political stability – but many do

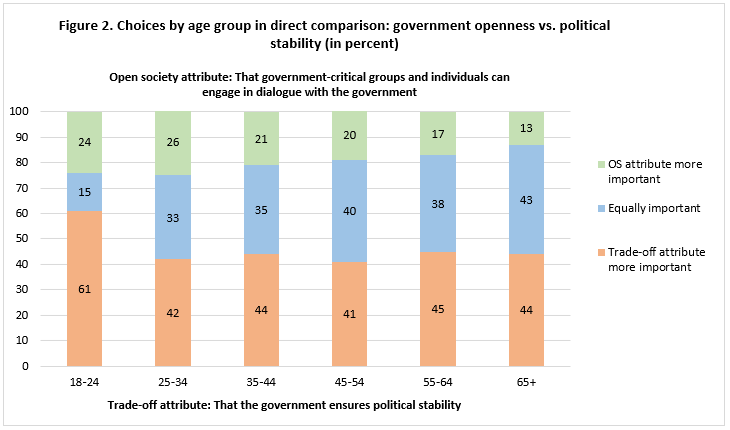

When asked whether a good society needed openness of government rather than political stability, 61 percent of young Germans said political stability was the most important. This is in line with other youth surveys showing that stability occupies an important place in young Germans’ understanding of a good society.

But for almost a quarter of the same age group, it was more important that groups critical of the government be able to engage in dialogue with the ruling parties. Out of all the age groups, the 18-to-34-year-olds are the most committed to government openness. But only 15 percent of 18-to-24-year-olds considered both aspects as equally important, while among all other age groups more than a third of respondents chose the in-between position.

Mixed news for the open society in Germany

What these patterns may mean is that young people – more so than older generations – are ready to make clear-cut choices about what constitutes a good society. This could be good news, but it also implies that for many young Germans there appears to be little room for consensus between those who support open society attributes and those who would rather see the government guarantee social cohesion, political stability and economic wellbeing. With fewer “in-betweens” defending both ends of the scale, young Germans may also be easier prey to simplistic yet effective populist discourse in the media and elsewhere, for instance that protecting minority rights is incompatible with security.

Above all, these results show that young people in Germany are not a homogeneous group. Germany’s young people are very different from the older generations in their views of what makes a good society. They are also more divided. This can change, of course, as values change over a lifetime, whether with age or different socio-economic circumstances.

But contacts made in a person’s younger years are widely considered to influence a lifetime of core values, like the kind of society a person wants to live in. According to social scientist Russell Dalton, “Once learned, values are stable beliefs and relatively impervious to later-life changes in the social or personal environments.” The values they consider most important may change over time, but a degree of division and polarisation among those Germans now aged between 18 and 24 is likely to persist.

This is mixed news for the open society, implying on the one hand that a substantial number of young Germans are, and will probably remain, firm supporters of open society values. On the other hand, a divided society is a society in which compromise is more difficult to reach and a common ground harder to find, two keys to an open and inclusive society. The biggest challenge for the future of the open society in Germany will be to bridge societal divides and to address the simplistic view that stability and openness are mutually exclusive.

If you want to read further:

Jugend 2015. 17. Shell Jugendstudie. Hurrelmann, A. M., K., Quenzel, K. G. & TNS Infratest, S. (2015). Frankfurt: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag.

Calmbach, M., Borgstedt, S., Borchard, I., Thomas, P. M. & Flaig, B.B. (2016) Wie ticken Jugendliche 2016? Lebenswelten von Jugendlichen im Alter von 14 bis 17 Jahren in Deutschland. Springer Link.

Dalton, R. (1981) The Persistence of Values and Life Cycle Changes. Politische Vierteljahreszeitschrift, Sonderheft ‘Politische Psychologie’.

Karakayali, S & Kleist, J. O. (2016) EFA-Studie 2: Strukturen und Motive der ehrenamtlichen Flüchtlingsarbeit in Deutschland, Forschungsbericht: Ergebnisse einer explorativen Umfrage vom November/Dezember 2015, Berlin: Berliner Institut für empirische Integrations- und Migrationsforschung (BIM), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

–

The author of this article, Magali Mohr, is a Research Fellow at d|part.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.